|

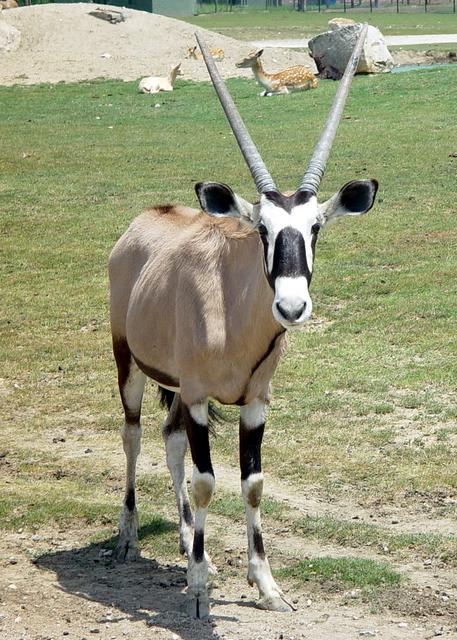

ANTELOPES AND DEER >> Gentle and Free Affections

GAZELLE >> Gracefulness of Affections

Several species of antelopes and deer are mentioned in the Bible under various names, which in our version are often mistranslated. Some of the species are not satisfactorily determined; but there seems to be no doubt that “hart” and “hind” are names rightly applied to the male and the female of true deer, perhaps of several species, and that the “wild roe” of our translation is the gazelle, one of the most familiar and graceful of antelopes. We will confine ourselves to these as types; and from these others will readily be distinguished when they are accurately known. Several species of antelopes and deer are mentioned in the Bible under various names, which in our version are often mistranslated. Some of the species are not satisfactorily determined; but there seems to be no doubt that “hart” and “hind” are names rightly applied to the male and the female of true deer, perhaps of several species, and that the “wild roe” of our translation is the gazelle, one of the most familiar and graceful of antelopes. We will confine ourselves to these as types; and from these others will readily be distinguished when they are accurately known.

Of antelopes, in general, Mr. Wood writes:

Resembling the deer in many respects, they are easily to be distinguished from those animals by the character of the horns, which are hollow at the base, set upon a solid core like those of the oxen, and are permanently retained throughout the life of the animal. Indeed, the antelopes are allied very closely to the sheep and goats, and, in some instances, are very goat-like in external form. In all cases the antelopes are light and elegant of body, their limbs are gracefully slender, and are furnished with small cloven hoofs. The tail is never of any great length, and in some species is very short. The horns, set above the eyebrows, are either simply conical, or are bent so as to resemble the two horns of the ancient lyre. (Natural History, “Antelopes”)

The gazelles of Palestine, Tristram thus describes from his own observation:

It is not so much because it yields savory meat as from its swiftness, grace, beauty, and gentleness that the gazelle is best known. . . . It is by far the most abundant of all the large game in Palestine; indeed it is the only wild animal of the chase which an ordinary traveler has any chance of seeing. Small herds of gazelle are to be found in every part of the country, and in the south they congregate in herds of near a hundred together. One such herd I met with at the southern end of the Jebel Usdum, or salt mountain, south of the Dead Sea, where they had congregated to drink of the only sweet spring within several miles, Ain Beida. Though generally considered an animal of the desert and the plains, the gazelle appears at home everywhere. It shares the rocks of Engedi with the wild goats; it dashes over the wide expanse of the desert beyond Beersheba; it canters in single file under the monastery of Marsaba. We found it in the glades of Carmel, and it often springs from its leafy covert on the back of Tabor, and screens itself under the thorn bushes of Gennesaret. Among the gray hills of Galilee it is still ‘the roe upon the mountains of Bether,’ and I have seen a little troop of gazelle feeding on the Mount of Olives, close to Jerusalem itself. While, in the open glades of the south, it is the wildest of game, and can only be approached, unless by chance, at its accustomed drinking places, and that before the dawn of morning, in the glades of Galilee it is very easily surprised, and trusts to the concealment of its covert for safety. I have repeatedly startled the gazelle from a brake only a few yards in front of me; and once, when ensconced out of sight in a storax bush, I watched a pair of gazelle with their kid which the dam was suckling. Ever and anon both the soft-eyed parents would gambol with it as though fawns themselves.

In Gilead, in the forest districts especially, . . . the ariel gazelle is extremely numerous, and in riding among the oaks we were continually putting up small troops. It is, if possible, a more beautiful creature than the common gazelle, of which it is now considered only a local variety.”

Of the ariel, Mr. Wood writes:

So exquisitely graceful are its movements, and with such light activity does it traverse the ground, that it seems almost to set at defiance the laws of gravitation, and, like the fabled Camilla, to be able to tread the grass without bending a single green blade. When it is alarmed, and runs with its fullest speed, it lays its head back, so that the nose projects forward, while the horns lie almost as far back as the shoulders, and then skims over the ground with such marvelous celerity that it seems rather to fly than to run, and cannot be overtaken even by the powerful, longlegged, and long-bodied greyhounds which are employed in the chase by the native hunters.

Some of the general characteristics of antelopes appear more clearly from the descriptions of several kinds. Of the springbok, a South African antelope, it is said:

The springbok is a marvelously timid animal, and will never cross a road if it can avoid the necessity. When it is forced to do so, it often compromises the difficulty by leaping over the spot which has been tainted by the foot of man. (Wood’s Natural History)

The pallah, another South African antelope:

. . . has a curious habit of walking away when alarmed, in the quietest and most silent manner imaginable, lifting up its feet high from the ground, lest it should haply strike its foot against a dry twig and give an alarm to its hidden foe. Pallahs have also a custom of walking in single file, each following the steps of its leader with a blind confidence.

The Indian antelope, or sasin:

. . . is a wonderfully swift animal, and quite despises such impotent foes as dogs and men, fearing only the falcon. . . . At each bound the sasin will cover twenty-five or thirty feet of ground, and will rise even ten or eleven feet from the earth, so that it can well afford to despise the dogs. . . . It is a most wary animal, not only setting sentinels to keep a vigilant watch, as is the case with so many animals, but actually detaching pickets in every direction, to a distance of several hundred yards from the main body of the herd.

Of the rhoodebok, Mr. Wood quotes from Capt. Drayson:

It is very amusing to watch the habits of this wary buck when it scents danger in the bush. Its movements become most cautious; lifting its legs with high but very slow action, it appears to be walking on tiptoe among the briers and underwood, its ears moving in all directions, and its nose pointed upwind, or towards the suspected locality. If it hears a sudden snapping of a branch, or any other suspicious sound, it stands still like a statue, the foot which is elevated remains so, and the animal scarce shows a sign of life for near a minute. It then moves slowly onwards with the same cautious step, hoping thus to escape detection.

The chamois of Switzerland are, perhaps, as shy of man as any antelopes. Of some that were domesticated as far as possible, it is related that they were “particularly inquisitive and curious, prying into everything”; and, what is probably in a greater or less degree characteristic of the family, “they would never suffer themselves to be touched; a finger not having yet reached them. They would admit of the hand being softly brought near their persons, but, immediately as it arrived within an inch of their head or body, they would vault, suddenly and lightly, from the proffered contamination.”

Most of these characteristics are common to antelopes and deer. “There is scarcely any animal,” Mr. Wood says, “so watchful as the female deer. It is comparatively easy to deceive the stag who leads the herd, but to evade the eyes and ears of the hinds is a very different business, and taxes all the resources of a practiced hunter” (Natural History). The desire to escape observation shows itself almost as soon as the fawn is born. “Mr. St. John relates that he once saw a very young red deer, not more than an hour old, standing by its mother, and receiving her caresses. As soon as the watchful parent caught sight of the stranger, she raised her forefoot, and administered a gentle tap to her offspring, which immediately laid itself flat upon the ground, and crouched close to the earth, as if endeavoring to delude the supposed enemy into an idea that it was nothing more than a block of stone.” Both antelopes and deer chew the cud and divide the hoof. They therefore were among the animals permitted for food, and correspond to some sort of kind and pleasant affections, not stimulating to the understanding merely, but encouraging to the heart. These affections are akin to the mutual love, charity, and helpfulness represented by sheep, goats, and oxen; but they love their own sweet will, and choose to show their graceful gentleness only in their own way, in entire freedom. The animals live in the forests and uncultivated plains, which represent the natural mind either unsubdued or in a state of rest. The Lord said to His disciples, “Come ye yourselves apart into a desert place, and rest awhile”; and the desert or uncultivated place represents the state of rest. The animals, therefore, are forms of impulses, gentle, kindly, attractive, and freedom-loving, made natural either by inheritance or by habit. The most graceful and attractive of them come and go almost like the thoughts, nearly intangible because of their shyness. Others are more sober and substantial; but none bend themselves to the steady work of life. Most of these characteristics are common to antelopes and deer. “There is scarcely any animal,” Mr. Wood says, “so watchful as the female deer. It is comparatively easy to deceive the stag who leads the herd, but to evade the eyes and ears of the hinds is a very different business, and taxes all the resources of a practiced hunter” (Natural History). The desire to escape observation shows itself almost as soon as the fawn is born. “Mr. St. John relates that he once saw a very young red deer, not more than an hour old, standing by its mother, and receiving her caresses. As soon as the watchful parent caught sight of the stranger, she raised her forefoot, and administered a gentle tap to her offspring, which immediately laid itself flat upon the ground, and crouched close to the earth, as if endeavoring to delude the supposed enemy into an idea that it was nothing more than a block of stone.” Both antelopes and deer chew the cud and divide the hoof. They therefore were among the animals permitted for food, and correspond to some sort of kind and pleasant affections, not stimulating to the understanding merely, but encouraging to the heart. These affections are akin to the mutual love, charity, and helpfulness represented by sheep, goats, and oxen; but they love their own sweet will, and choose to show their graceful gentleness only in their own way, in entire freedom. The animals live in the forests and uncultivated plains, which represent the natural mind either unsubdued or in a state of rest. The Lord said to His disciples, “Come ye yourselves apart into a desert place, and rest awhile”; and the desert or uncultivated place represents the state of rest. The animals, therefore, are forms of impulses, gentle, kindly, attractive, and freedom-loving, made natural either by inheritance or by habit. The most graceful and attractive of them come and go almost like the thoughts, nearly intangible because of their shyness. Others are more sober and substantial; but none bend themselves to the steady work of life.

Such affections from inheritance abound in youth of both sexes, and produce light, graceful, shy manners in girls, polite, courteous behavior in young men, and the pleasant, quick-witted gambols of both—innocent and entertaining, but utterly averse to labor or method. They are distinguished from the wild-ass affections that belong to the same age, in that they are not rude, critical, and contemptuous of others, but are gentle and affectionate, and desirous of pleasing. Such affection made natural from a spiritual origin is thus described: In the lamentation of David over Saul and Jonathan, he says, “The gazelle of Israel is slain upon thy high places; how are the mighty fallen! . . . How are the mighty fallen in the midst of the battle! O Jonathan, slain in thine high places. I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan; very pleasant hast thou been to me; thy love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women” (2 Samuel 1:19, 25, 26). Such affections from inheritance abound in youth of both sexes, and produce light, graceful, shy manners in girls, polite, courteous behavior in young men, and the pleasant, quick-witted gambols of both—innocent and entertaining, but utterly averse to labor or method. They are distinguished from the wild-ass affections that belong to the same age, in that they are not rude, critical, and contemptuous of others, but are gentle and affectionate, and desirous of pleasing. Such affection made natural from a spiritual origin is thus described: In the lamentation of David over Saul and Jonathan, he says, “The gazelle of Israel is slain upon thy high places; how are the mighty fallen! . . . How are the mighty fallen in the midst of the battle! O Jonathan, slain in thine high places. I am distressed for thee, my brother Jonathan; very pleasant hast thou been to me; thy love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women” (2 Samuel 1:19, 25, 26).

It seems to be Jonathan who is called the gazelle of Israel; for the same expression, “slain upon thine high places,” is applied to him only. And his representation must be natural delight in the protection of the Lord, through the truth.

Saul represents the natural reason to which the kingdom of the mind is first entrusted, and which is dethroned because it decides for itself instead of patiently discerning and obeying the truth from the Lord. Yet from this understanding, even through its disappointments, is begotten the truth that wisdom of life is from the Lord alone, and a happy trustfulness in having it so. This is represented by the light-hearted, generous Jonathan, whose very name means “the gift of Jehovah.” But not to Jonathan was the kingdom given; for not his was the patient application of the truth to life, which was represented by David. “He stripped himself of the robe that was upon him, and gave it to David, and his garments, even to his sword, and to his bow, and to his girdle.” He knew that in doing this he was giving him the kingdom; and he meant it, and asked nothing for himself but that David should be kind to his children (1 Samuel 20:15). With characteristic solitariness and trustfulness, attended only by his armor bearer, he attacked a strong garrison of the Philistines, saying, “It may be that the Lord will work for us; for there is no restraint to the Lord to save by many or by few” (1 Samuel 14:6). And afterwards, when he innocently brought upon himself his father’s curse by tasting of the forbidden honey as he passed, so attractive was his generous chivalry to the people, that they rescued him from death, and took upon themselves the curse.

There was dutifulness also with his romantic affection; for when his beloved friend was persecuted and fled, Jonathan turned faithfully back to his father, and for him fought valiantly, and with him laid down his life upon Mt. Gilboa.

The same Hebrew word that means a “gazelle” is often translated “beauty,” and sometimes “glory”; probably because the gazelle was so marked a type of beauty. In these cases it represents the gracefulness of affections that have become easy and natural.

But natural good affection is not always from the Lord, sometimes being insincere and interiorly selfish; and such affection is meant by the chased gazelle (or roe) in Isaiah. “Therefore I will shake the heavens, and the earth shall remove out of its place, in the wrath of the Lord of Hosts, and in the day of His fierce anger. And it shall be as the chased roe, and as a sheep that no man taketh up” (Isaiah 13:13, 14), speaking of the judgment, in which merely external and hypocritical forms of goodness will be dispersed.

The horns of antelopes are permanent, and are composed of fibrous, hairy horn, like those of our domestic animals. They represent the knowledge which these affections possess of the delightfulness and propriety of their free impulses, which they use in self-defense, and sometimes in friendly rivalry. The horns of deer are very different in form and material; the animals are generally somewhat larger in size, inhabit more northerly homes, and possess more variable tempers; some of them also, as the reindeer, are so far domesticated as to be of service to owners who will follow them in their necessary migrations. Their horns are thus described by Mr. Wood:

The horns of deer belong only to the male animals, are composed of solid, bony substances, and are shed and renewed annually during the life of the animal. The process by which the horns are developed, die, and are shed, is a very curious one. . . . In the beginning of the month of March the stag is lurking in the sequestered spots of his forest home, harmless as his mate and as timorous. Soon a pair of prominences make their appearance on his forehead, covered with a velvety skin. In a few days these little prominences have attained some length, and give the first indication of their true form. Grasp one of these in the hand, and it will be found burning hot to the touch; for the blood runs fiercely through the velvety skin, depositing at every touch a minute portion of bony matter. More and more rapidly grow the horns, the carotid arteries enlarging in order to supply a sufficiency of nourishment, and in the short period of ten weeks the enormous mass of bony matter has been completed. Such a process is almost, if not entirely, without a parallel in the history of the animal kingdom. When the horns have reached their due development, the bony rings at their bases, through which the arteries pass, begin to thicken, and by gradually filling up the holes, compress the blood vessels, and ultimately obliterate them. The velvet now having no more nourishment, loses its vitality, and is soon rubbed off in shreds against tree trunks, branches, or any inanimate objects. The horns fall off in February, and in a very short time begin to be renewed. These ornaments are very variable at the different periods of the animal’s life, the age of the stag being well indicated by the number of “tines” upon his horns. (Natural History “Deer”)

Of the moose, or elk, he writes:

It is as wary as any of the deer tribe, being alarmed by the slightest sound or the faintest scent that gives warning of an enemy. . . . Generally the elk avoids the presence of man, but in some seasons of the year he becomes seized with a violent excitement that finds vent in fighting with every living creature that may cross his path. His weapons are his horn and forefeet, the latter being used with such terrible effect that a single blow is sufficient to slay a wolf on the spot. (Natural History)

The reindeer in its wild state is a migratory animal, making annual journeys from the woods to the hills, and back again, according to the season. . . . Even in the domesticated state, the reindeer is obliged to continue its migrations, so that the owners of the tame herds are perforce obliged to become partakers in the annual pilgrimages. (Natural History) The reindeer in its wild state is a migratory animal, making annual journeys from the woods to the hills, and back again, according to the season. . . . Even in the domesticated state, the reindeer is obliged to continue its migrations, so that the owners of the tame herds are perforce obliged to become partakers in the annual pilgrimages. (Natural History)

The wapiti, or Carolina stag, lives in herds of variable numbers, some herds containing only ten or twenty members, while others are found numbering three or four hundred. These herds are always under the command of one old and experienced buck, who exercises the strictest discipline over his subjects, and exacts implicit and instantaneous obedience. When he halts, the whole herd suddenly stops; and when he moves on, the herd follows his example. . . . This position of dignity is not easily assumed, and is always won by dint of sheer strength and courage, the post being held against all competitors at the point of the horn. The combats that take place between the males are of a singularly fierce character, and often end in the death of the weaker competitor. An instance is known where a pair of these animals have perished, . . . their horns having been inextricably locked together. (Natural History)

Of the Virginian deer, or carjacou:

The male is a most pugnacious animal, and engages in deadly contests with those of his own sex. . . . In these conflicts one of the combatants is not infrequently killed on the spot, and there are many instances of the death of both parties in consequence of the horns interlocking within each other, and so binding the two opponents in a common fate. To find these locked horns is not a very uncommon occurrence, and in one instance three pair of horns were found thus entangled together, the skulls and skeletons lying as proofs of the deadly nature of the strife. It is in October and November that the buck becomes so combative, and in a very few weeks he has lost all his sleek condition, shed his horns, and retired to the welcome shelter of the forest. (Natural History)

In the parting blessing which Jacob pronounced upon his sons, he said, “Naphtali is a hind let loose, speaking words of elegance.” Naphtali signifies strugglings, or, spiritually, temptations. And, as Swedenborg remarks, “Liberation from a state of temptations is compared to a hind let loose, because the hind is a forest animal, loving liberty more than others, to which the natural also is similar, for this loves to be in the delight of its affections, hence, in freedom, for what is of affection is free” (Arcana Coelestia #6413).

He also says that these words describe “the state after temptation as to the spontaneous eloquence which results from perception” (Arcana Coelestia #9413, 3929).

Perhaps the gentle, free affections which deer represent differ from those signified by antelopes in this, that their gentleness, freedom, and beauty are the result of trials and temptations. The periodically irritable, contentious, moody states of deer are likenesses of states of temptation, which are followed by times of humility and shyness, and then by new confidence, happiness, and freedom, the right to which is defended by branching antlers, not of truth perceived and known concerning itself, like the horns of antelopes, but of the very substance of its bones, from the facts of its own life, to which every new round of experience adds a new array. These at length become the means by which it contends for superiority and precedence, and then in conscious weakness it lays them down, and retires in mortification.

The fleet and confident steps of affection that has become free and natural are thus described in the Word: “He maketh my feet like hinds’, and setteth me upon my high places” (Psalm 18:34). “The Lord Jehovih is my strength; He maketh my feet like hinds’, and maketh me to walk upon my high places” (Habakkuk 3:19).

Again, it is written concerning the effect of the coming of the Lord, “Then shall the lame man leap as a hart” (Isaiah 35:6), referring to those who from ignorance or from lack of good love find the way of good life painful and difficult, but, as it were, leap with confident strength and pleasure when good love from the Lord becomes natural to them.

And once more we read, “As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after Thee, O God” (Psalm 42:2), where the feverish desire of the soul in time of temptation, for cooling and consoling truth, is compared to the thirst of the hart, which in the dry season must make long journeys to the lessening streams.

Author: JOHN WORCESTER 1875

|

|